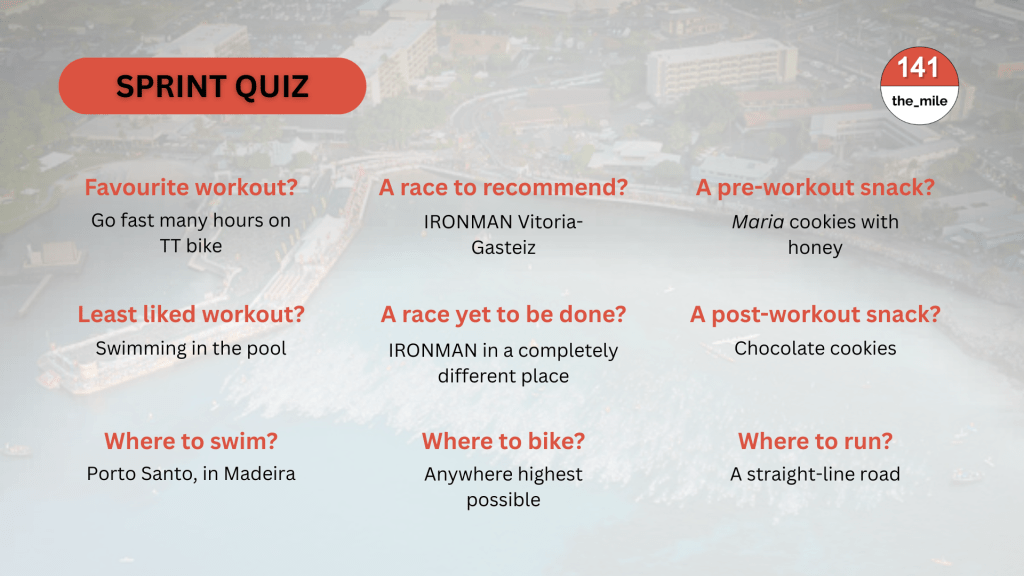

Interview: Mario André Bastos Rocha

Entrevista em Português aquí

Born in Aveiro in 1993, Mario André is one of the leading triathletes on the Portuguese amateur scene. He has won numerous races and podiums across all distances, both at the age group and absolute (amateur) levels. The culmination of his sporting career, at least for the moment, came last year with the victory in the AG 30-34 at Ironman Vitoria-Gasteiz, being second among all age groupers, with a time of 8h33. He lives and breathes the sport, combining his training with his profession as triathlon coach.

You are Portuguese and live in Portugal, but you spent many years in Brazil. What was that time in your life like?

I went there with my mom when I was 15 and, going back a bit to the start of my sports journey, I lived in João Pessoa city, in Paraíba state, near the beach, where there was a lot of sports activity. Thus, I decided to buy a pair of running shoes and ended up starting to run on my own. Eventually, I got in touch with a club — assessoria desportiva, as they are called there — which invited me to run for them and helped me with training planning.

In total, I spent eight years in Brazil, because I returned when I was 23. It was always a period of adaptation. I always had my work in the restaurant with my mom and my secondary studies there, but there are always new things in a country you do not know, especially because my sporting activity kept changing… From running I moved on to MTB (mountain bike), and then only in the last four years I got to know triathlon. It was truly a country that allowed me to discover sport.

That is where you started with triathlon. What do you remember from those early triathlon days?

I joined a group that was training for their first Ironman in just over nine months… and they were all almost as inexperienced as I was. They did their first race together with mine.

At the beginning, let’s just say there was not much time to adapt because I only had about three months to prepare for my first Olympic triathlon in the city, which was a national championship. I said “Well, why not, let’s give it a go…”. Then it all was very much in the dark. Of course, I was already training, I already had a solid running and cycling base, but very little to no swimming. So those were three intensive months with training, also in open water mainly, because there we always have that possibility of training in the sea.

So you decided you wanted to continue in triathlon…

Triathlon is a sport that is multifactorial, in the sense that you do not always have to do the same thing. For me and my mind, it suited my profile better, since I cannot stick to doing just one thing.

Therefor it became much more attractive and never boring, because I was doing a different sport every day. The fact that I could switch from one sport to another within a single training session was what fascinated me most. It was not many hours of training… about 8–10 hours per week.

I had to sell my MTB bike and look for alternatives and equipment needs. It was all very improvised, but with a new goal in a short time and aiming to speed up the process to achieve the best outcome possible.

Running, MTB, triathlon… Is there any other sport that catches your attention or that you would like to try at some point in your life?

No. That is, no sport outside the three disciplines that make up triathlon. Of course, there are other sports that catch my attention, but thinking about doing them seriously or taking them further, not really.

I do not see myself doing anything else right now. I would love to innovate in the future within one of the triathlon disciplines or in some long or extreme distance races. Not so much trail running, but maybe more toward ultra-distance cycling or even some ultra-distance running.

I would also like to do an ultra-triathlon, without it being too tedious. For example, in Brazil there is one where the cycling course is just over 5–6 km per lap. So you end up doing 300 laps of the circuit… Anyway, I still have to explore, but it is not something for right now. Maybe in ten years.

You returned to Portugal, and that did not stop you from continuing in sport. What are the differences between practicing triathlon in Brazil and in Portugal?

In Brazil there is a very large sports community. Cities breathe sport in a different way than in Europe. There is greater unity among clubs and more transparency among athletes. You are at the beach and there are about ten clubs doing the same sport. It is almost instinctive, you feel compelled to do sports. Here in Portugal, we are always more closed within structures and do not communicate much outwardly.

The main difference has a lot to do with the possibility of training outdoors year-round, although indoor training may still be included in the plan to limit heat exposure. On the other hand, there are setbacks as well: commuting is difficult due to some cities are very large, safety when training alone — due to thefts, etc. — as well as fear because of traffic, as there are many accidents.

And in terms of competition? Are there similarities?

There are very few races and access is extremely difficult. Sometimes it takes days of travel to compete in a national championship. I remember, for example, I ended up buying a flight with three connections because it was cheaper. I literally spent 26 hours traveling to compete two days later. I left the northeast of Brazil, went to Rio de Janeiro and from Rio I had to go to the midwest, then to the north of Brazil, and then a three-hour bus ride.

So not everyone has access to competitions. I would say that 50% of athletes in Brazil choose just one race per year. The rest is training and simply living the sport.

8 hours, 33 minutes and 36 seconds. What do those numbers mean to you?

Well, it is above all something I always dreamed of, but never expected to achieve… Maybe 6–7 years ago it was something I was pursuing intensely because I went through a period where I wanted to become a professional and trained with that goal.

However, I had a brief two-year break in the middle of the twelve I have spent in triathlon; I came across a job opportunity as manager of a sports shop here in Aveiro, and at that time I did not have much time to train. When I came back it was different; those were not the goals anymore. It was more about doing my best and enjoying the sport. But the competitive root is always inside me, and whenever I restart a specific training cycle, that competitive side wakes up. And the truth is, hitting 8h30 in an Ironman (Vitoria-Gasteiz 2024) was something that I thought might be the peak of my career.

That result made me disconnect for a few months and rethink what I wanted to do and what my future goals would be. I believe that after achieving that, I felt I might be able to do even better, so… let’s see what this year brings.

At 31 years old, there must still be room to improve. Where do you think your limits are?

The truth is, to reach 8h to 8h20 in an Ironman I would need to consider a different lifestyle, mainly with more rest. Especially mental rest and peace of mind that would allow me not to always be racing against the clock.

That is, for me, many training sessions are done right after working at the computer or right after dropping off my son at school at 9am, I am already planning to be on the bike by 9:15. I do not have time to relax after training, cool my head, and get back to work. No, it is get home, shower, and back to the computer or to coaching.

Thus, I would say the main factor is not the number of hours I could dedicate to sport, but the number of quality hours I could dedicate to training and resting.

The performance of both professionals and amateurs has improved drastically in recent years, especially in younger age groups. What do you think is behind this progress?

One of the main reasons is the fact that many athletes from other sports are switching to triathlon, due to its dynamism. Also, the exchange of information — knowing how to train. Different from past, nowadays there is a training plan designed with triathlon strategies, to understand how one workout affects the other. In the end, since it is an endurance sport and very trendy, I believe that has driven huge evolution.

But deep down, what I believe in most, more than all those factors, is nutrition, especially at the professional level. I attribute the massive breaking of records, not just in triathlon but in all endurance sports, to nutritional control — before races, during training, etc. I know that has changed completely in the last five years, especially in terms of recovery for the next workouts.

You compete at top amateur level in Portugal, always finishing near the top. That gives you insight into your direct rivals. Is there anyone you would highlight? For their skill, dedication, or personal qualities, for example.

There are quite a few triathletes I am connected to in some way, but right now I believe Henrique Moreira, from Clube dos Galitos — the triathlon club where I am the coach — ends up being the standout amateur athlete at the moment.

Also, since I started my sports journey in Portugal, I have always been impressed by Sérgio Marques, who, despite having had a professional phase, still competes as an amateur. And even though in the last two years he has felt like he is not at the same level, he still performs at a very high standard.

Among your most immediate goals are the Long Distance World Championship in Pontevedra and Ironman Emilia-Romagna. What are your expectations?

Well, it could not be any other way — if I go to a World Championship, it is to become champion in my age group. My expectations are quite high, as long as I do what I feel and apply what I trained last year for the Ironman. Also, in terms of training, there are a few factors that make me believe I am in better physical shape now than I was for Ironman Vitoria. But then again, they are different profiles, different races, different places — and all of that carries a lot of weight.

The World Championship is the main goal of the season, although the Ironman brand has its own weight in terms of media exposure. So, even if I do not manage a great result at the World Championship or the result I have in mind, I still have a second chance. If I win the World Championship, I will probably feel less pressure for the Ironman goal. Let’s put it this way: I would not have anything to prove to anyone anymore — not that I ever do, but I at least have to prove to myself that this year I achieved a good result.

One interesting aspect of your training is that you never do any physical exercise, absolutely none. What can you tell us about that?

I have a very silly record because when I started in triathlon, I was also going to the gym. One thing I did a lot was the fixed front plank. There was a lady around fifty years old who started competing with me. I held four minutes, she did six, then I did seven, she did eight… When she reached eight, I said: “It is all or nothing”. So I prepared myself for about a month. I was always doing ten to fifteen minutes, until I finally thought: “It is time”. I put on headphones, played music, and stayed still for 40 minutes staring at a stopwatch on the floor…

Another thing I did a lot back then was stretching and mobility. I had the nickname “elastic man” or “rubber man” because, like gymnasts, I could easily do the splits.

All this to say that I think if a movement for muscle conditioning is not natural, it often ends up causing more harm than strengthening. A muscle without proper stretching is a muscle that has not reached its full potential for strength training. I never did [strength training], and I have never been injured (except due to wearing inappropriate running shoes) but it is not something I recommend for most people, since it is necessary to develop other muscle groups to perform the specific movements of the sport more correctly.

Professionally, you run your own business as a triathlon coach. It is clear this is your passion and your goal is to dedicate yourself to it for a long time. Is that right?

Yes. It is a recent project in terms of execution, but it is an old project in my mind. In everything I have always done in sports, there was a clear passion for passing on the message and the passion. I did not know how — whether I should be a coach or something else or simply be part of a club and contribute.

But the awakening of triathlon and endurance sports more broadly allowed me to see that there was a window of opportunity in this field and led me to decide this was my path for the future. I am not sure if it will always be my path, but probably, yes.

On the other hand, you also have a coach, with his own training philosophy. How do you balance your knowledge with that of a colleague?

For my athletes, I look at numbers and data a lot. For me, I am not an athlete who compares week to week using numbers. I am an athlete who compares based on sensations and mental state. I think that is the key.

What I mean is, I do not debate with the coach about any specific training. I just make sure there is progress and good feelings week by week. I know what volume I need to add and, for me, when in doubt, training volume is king, regardless of whether the zones are right or whether a certain training zone is being emphasized. If the volume and the sensations are in line with my goals, I stay firm, trust the process, and I also believe it would work with this coach or probably any other.

As a result of your work, you get to live the daily life of athletes first hand. What mistakes do you see most often?

The main mistake is expecting immediate results — trying to reach certain benchmarks too quickly, or, for example, wanting to replicate in triathlon the pace and numbers from individual sports.

I would say that, to reach a certain level of performance and consistency, you need at least one to two years of training — and with an athletic background already. Skipping these steps is, for me, one of the biggest mistakes most triathletes make. There are so many variables in races that trying to replicate your best performance across different types of races is not realistic.

Then there is the mistake of athletes who are not able to correlate the necessary training hours with their habits — sleep, diet, work, routine. People end up looking for gear and shortcuts and want to attribute their athletic improvements to that. I would not even call them mistakes — it is just a lack of clarity and understanding about what solid performance really takes.

Do you have any interesting anecdotes from your athletes to share?

It was not someone very close to me, but I once met an athlete whose main goal was to finish Ironman Brazil and earn the medal.

So, the bike leg went pretty bad. He had what you could call a full shutdown. And what happened was… the hotel was by the course of the race. He went to the hotel, dressed as an Ironman, took a shower, ate, slept for about 30 minutes, then went back out and finished the race in 15 hours. All good. He wanted to do it in 10 hours, but the ultimate goal was to finish. Slept, ate, came back.

Another athlete did something similar last year in Sines. He vomited, went to the ambulance, the doctors checked him and said everything was fine. But the ambulance had already taken him further than where he was on course before. And he, not wanting to cheat or take advantage, not only got out of the ambulance with time lost but also went back and covered the extra distance the ambulance had moved him, then resumed and finished the race.

They say teaching is learning. What do your athletes teach you?

Well, it really depends on the athlete, but many of them teach me to give more. By seeing in others how difficult it is to have a job with a more demanding schedule and still find the resilience and willpower to train many hours.

They try to reach certain goals and keep training, each one with their own lifestyle, work demands, family logistics and so on. The fact that each one manages, in their own way, to practice a sport as difficult as this — because of how much it demands in so many areas —, that is what I take away from triathlon and my athletes.

Next interview:

Camille King (France/UK)

Leave a comment